Pericardial Disease Center

What is Pericarditis?

The pericardium is a protective, fluid-filled sac that surrounds the heart. It supports proper heart function and protects the heart from infection and trauma. Pericarditis is inflammation of the pericardium. Pericarditis is characterized by chest pain with associated electrocardiographic changes and usually pericardial effusion (fluid in the pericardium).

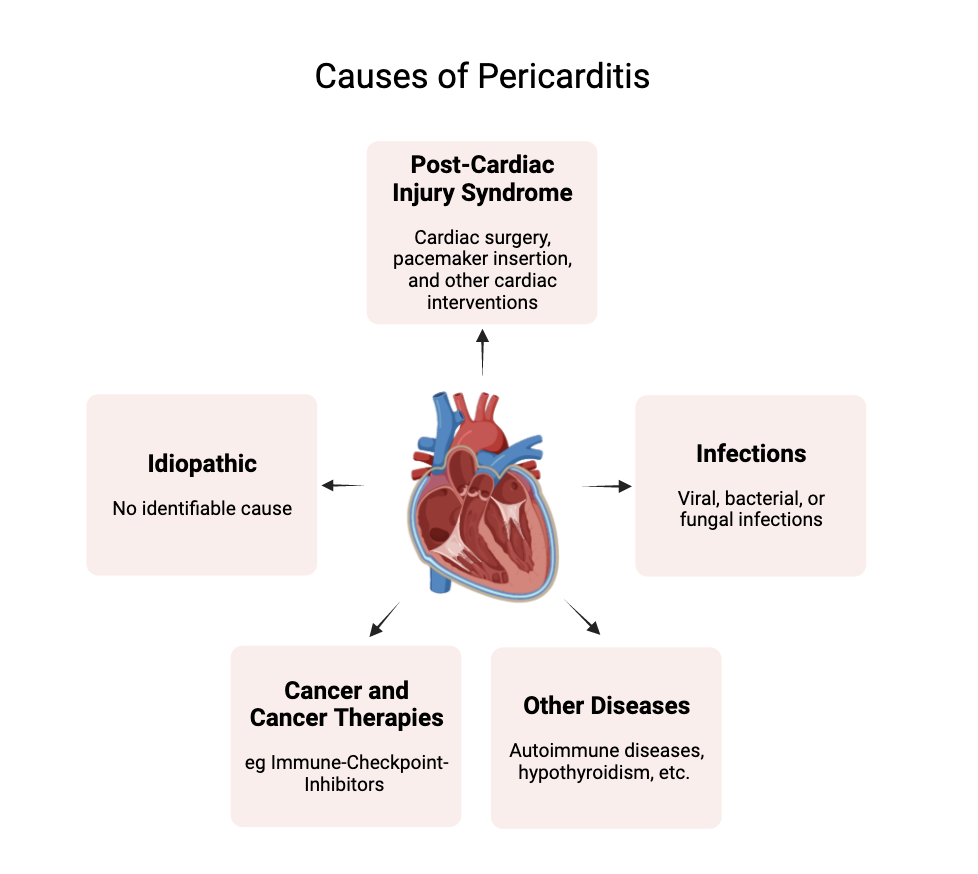

Pericarditis can result from various factors such as infections, post-cardiac injury syndrome, autoimmune disease, cancer and cancer treatments. In most cases, there is no cause identified and these cases are considered idiopathic.

- Idiopathic: For some cases of pericarditis there are no known causes. This makes up for about 55% of patients diagnosed with pericarditis.

- Post-cardiac injury: Pericarditis can be caused by post-cardiac injuries from various cardiac testing and interventions. For example, pericarditis can be caused as a result of cardiac surgery, pacemaker insertion, radiofrequency ablation, transcatheter aortic valve implantation, and, rarely, percutaneous coronary intervention. Post-cardiac injury related pericarditis makes up for about 20% of patients diagnosed with pericarditis.

- Infection: Pericarditis can originate from various bacterial, viral, and fungal infections. These include myobacterium tuberculosis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Coxsackievirus, Echoviruses, Adenoviruses, Herpesviruses (EBV, CMV), HIV, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA), Candida, and Histoplasma capsulatum. Infection related pericarditis makes up for about 14% of patients diagnosed with pericarditis.

- Cancer and cancer therapies: Conditions characterized by rapidly dividing cells, commonly referred to as cancer, can lead to pericarditis when the heart becomes a target of inflammatory immune cells. This inflammation can result directly from the cancer itself or from cancer treatments, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and radiation therapy. Cancer-related pericarditis accounts for approximately 5% of all pericarditis cases.

- Other diseases: Autoimmune disorders and hypothyroidism are additional conditions that can lead to pericarditis, as they involve the immune system attacking the body, with the heart being a specific target. Disease related pericarditis accounts for approximately 5% of all pericarditis cases.

Types of Pericarditis

Pericarditis is classified into four types based on timeline of symptoms: acute, incessant, chronic, and recurrent. Acute pericarditis may recur in 20% to 30% of cases, and half of these patients may experience multiple recurrences. Incessant pericarditis lasts for more than 4 to 6 weeks without a symptom-free period. Recurrent pericarditis involves new symptoms appearing after a break of 4 to 6 weeks. Chronic pericarditis persists for over three months.

Acute Pericarditis

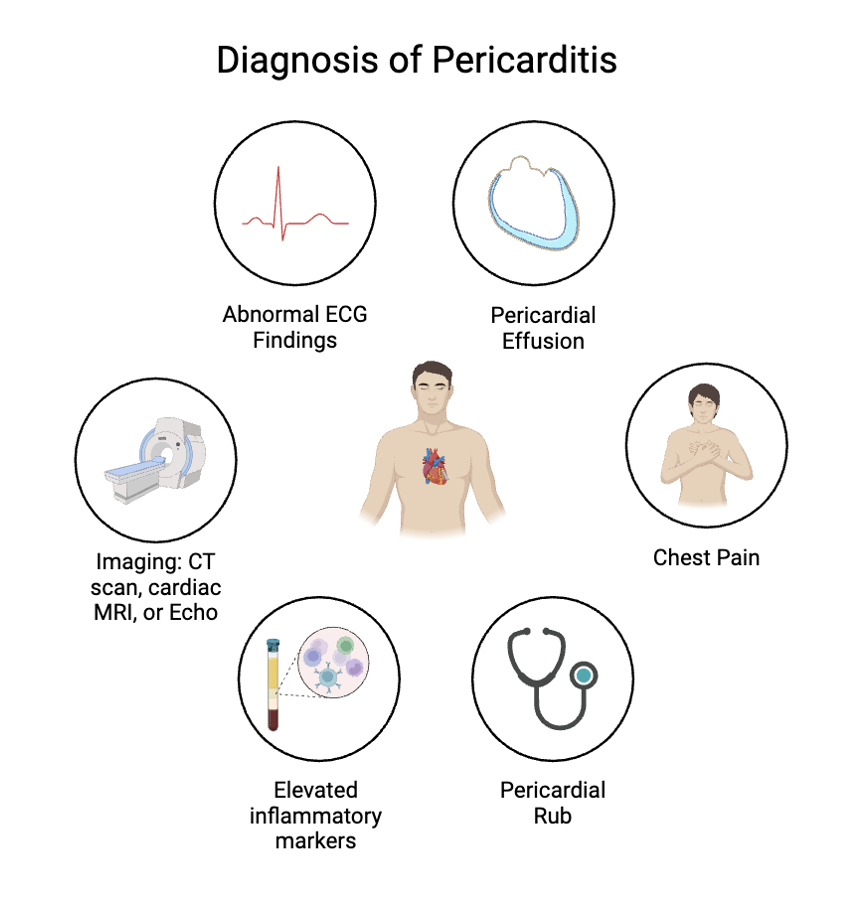

Acute pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease. There are four diagnostic criteria for pericarditis: chest pain that is typical for pericarditis (positional, pleuritic), a distinctive sound from the heart (pericardial rub), new widespread changes in the heart's electrical activity on an electrocardiogram (ST-segment elevation or PR depression), and new or worsening fluid around the heart (pericardial effusion). Additional supportive signs include high levels of inflammation markers in the blood and evidence of pericardial inflammation on imaging tests like CT or cardiac MRI.

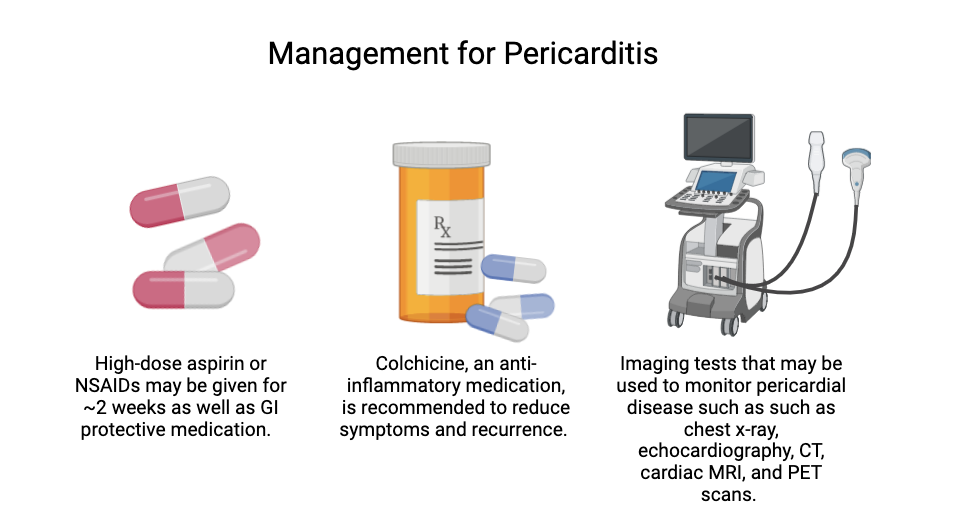

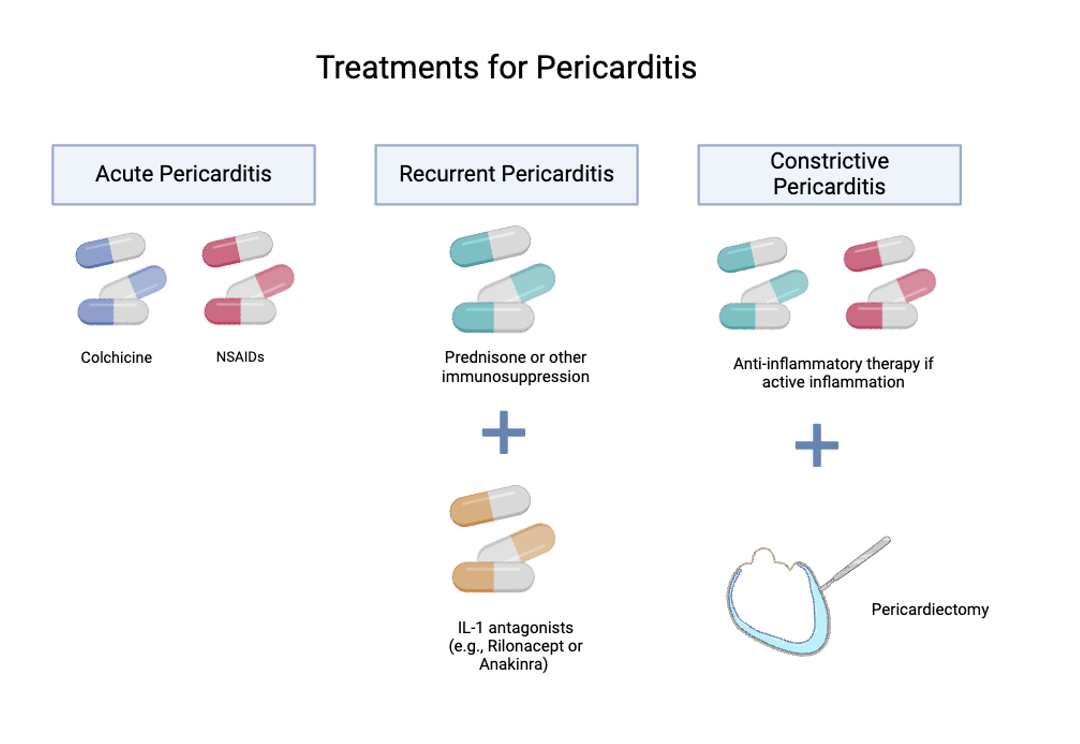

Treatment for acute pericarditis typically involves taking high-dose aspirin or NSAIDs for about 2 weeks, with medications to protect the stomach. Colchicine (another anti-inflammatory medication) is also recommended to help reduce symptoms and recurrence. Imaging tests that may be used to monitor pericardial disease include chest x-ray, echocardiography, CT, cardiac MRI, and PET scans.

Low-risk patients can usually be treated at home, while those with one or more risk factors may need to be hospitalized (such as patients with a large pericardial effusion or with evidence of heart inflammation). Patients are considered high risk if they have a fever over 38°C, large fluid buildup around the heart, heart compression (cardiac tamponade), or no improvement after one week of anti-inflammatory treatment.

Recurrent Pericarditis

Acute pericarditis can recur in 20% to 30% of cases, and among those who experience a recurrence, up to 50% may have additional episodes. Recurrent pericarditis is thought to be an immune-mediated phenomenon after incomplete treatment of the initial pericarditis. The clinical presentation of recurrent pericarditis is similar to acute pericarditis; diagnosis requires a symptom-free interval of 4 to 6 weeks and evidence of new pericardial inflammation. Patients are often treated with colchicine, and corticosteroids or other immunosuppression such as IL-1 blockade (example: rilonacept).

Pericarditis can lead to complications such as cardiac tamponade, where fluid buildup compresses the heart, and constrictive pericarditis, where the pericardium becomes stiff. The risk of developing constrictive pericarditis increases with chronic inflammation. Constrictive pericarditis can develop with or without fluid buildup (effusion). Diagnosis typically involves echocardiography in patients with a history and physical findings suggesting high clinical suspicion. Symptoms may include fatigue, exercise intolerance, dyspnea, anorexia, and heart failure.

Surgical options for pericardial diseases include creating a pericardial window to drain fluid into the pleural space and to prevent tamponade, and pericardiectomy (surgical removal of the pericardium) for treating constrictive pericarditis.

Pericardial Effusions in Cancer Patients

What is Pericardial Effusion?

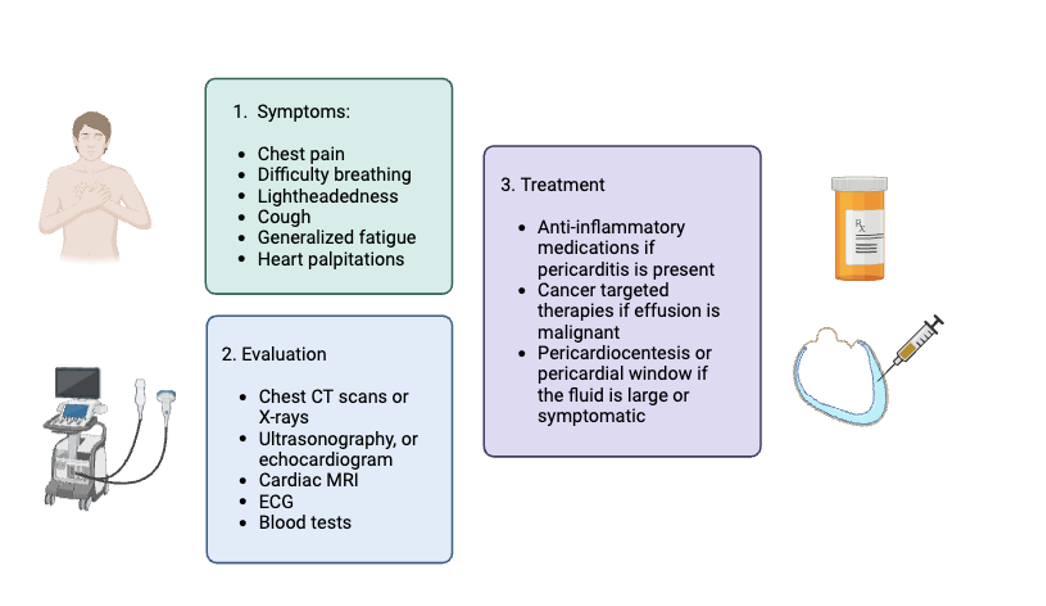

Fluid in the pericardial space is called a pericardial effusion. A pericardial effusion occurs when too much fluid builds up in the sac around the heart, called the pericardium. Normally, there is a small amount of fluid in the pericardial space, but certain conditions like infections, autoimmune diseases, trauma, kidney disease, pericardial inflammation, medication side effects, or cancer can cause extra fluid to gather. If the fluid builds up slowly, patients might not notice any symptoms. But if it builds up quickly or if there is a lot of fluid, patients may experience various symptoms including shortness of breath, cough, chest pain, palpitations (heart racing), dizziness, and lightheadedness.

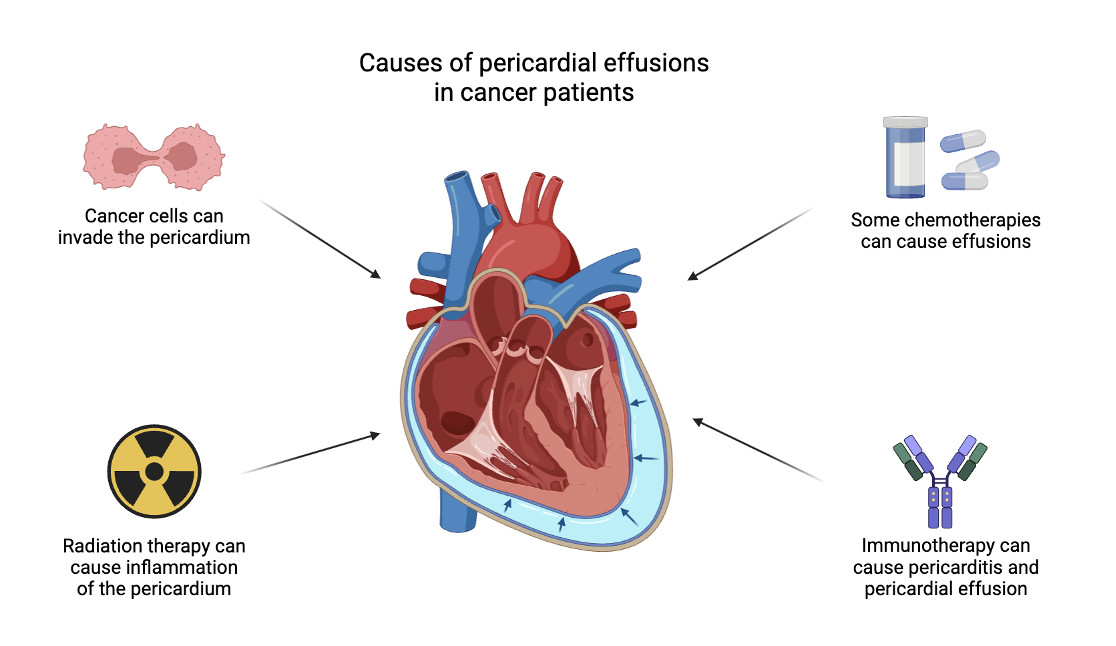

Why Are Cancer Patients at Risk?

In cancer patients, the most common reason for a pericardial effusion is when cancer spreads to the pericardium. This is called a malignant pericardial effusion. Certain cancers are more likely to cause a malignant pericardial effusion, including lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, pancreatic cancer, melanoma, and certain blood cancers, especially B-cell lymphoma. Sometimes, cancer can also block the lymph nodes in the chest, which impairs proper draining of fluid, leading to a buildup of fluid around the heart.

Cancer treatments can also cause fluid to build up around the heart. Some chemotherapies can cause this problem, including drugs like anthracyclines, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, busulfan, cytarabine, and cyclophosphamide (among others), particularly when used in high doses or in combination with other cancer therapies. Additionally, fluid around the heart has been reported with the use of immune therapy drugs, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (for example, pembrolizumab). Radiation therapy to the chest can lead to a pericardial effusion due to inflammation of the pericardium itself.

How Should You Monitor for Pericardial Effusions? What Are Treatment Options?

Pericardial effusion is often found incidentally (without symptoms) in cancer patients when they have heart or chest scans for other reasons. Chest imaging (such as CT scans and X-rays) might show a pericardial effusion or an enlarged heart size, and an electrocardiogram (ECG) could show signs that suggest fluid around the heart. However, the best way to diagnose it is with a heart ultrasound called an echocardiogram.

Treatment for pericardial effusion depends on the cause and how the symptoms develop. If the pericardial effusion is caused by inflammation of the pericardium (called pericarditis), this is treated with anti-inflammatory medications, such as high dose NSAIDs and colchicine. If the symptoms are mild or the effusion is not rapidly accumulating, doctors may recommend monitoring the fluid with regular heart ultrasounds (echocardiograms). For cancer-related fluid buildup around the heart, treating the cancer with chemotherapy or radiation is important, as it can help stop the fluid from coming back. If the fluid is large or if there is uncertainty about the cause of the effusion, doctors might recommend draining the fluid with a pericardiocentesis. In some cases, doctors might recommend a procedure to create an opening in the pericardium (pericardial window) so that the fluid continuously drains out of the pericardial space.

Larger fluid buildups can lead to a serious condition called tamponade, where the pressure from the fluid prevents the heart from pumping blood properly. This is a medical emergency that requires urgent drainage of the fluid.

Management of Patients with Pericardial Disease at UCSF

Our team members are experts in Cardio-Oncology and Immunology, particularly interested in evaluating and managing pericardial disease. The UCSF Pericardial Disease Center is led by Dr. Alan Baik (UCSF profile), and other members of the team include Dr. Javid Moslehi, Dr. Mandar Aras, and Dr. Amy Lin. We use a multidisciplinary approach to better understand pericardial disease and to develop personalized treatment strategies. We are also actively involved in research to better understand the factors that lead to pericardial disease, such as pericardial effusions and recurrent pericarditis. Our clinic is one of the sites involved in the national American Heart Association Recurrent Pericarditis Initiative.

To learn more about our faculty members, click here: Cardio-Oncology Faculty

Ongoing Research

UCSF is actively engaged in various research initiatives to better understand the mechanisms of pericarditis and to identify biomarkers of pericardial disease progression. One key area of research involves identifying the underlying causes of pericarditis, with the goal of developing novel diagnostics and treatments. The INFLAME Biorepository is one of our biobanks in which we gather biospecimens from individuals suspected or confirmed to have pericarditis, aiming to enhance our understanding of the biological attributes of inflammatory heart conditions, including pericarditis and myocarditis.

How to Refer

For outpatient referrals:

To refer a patient to a Cardiologist:

Phone: (415) 353-2973

Fax: (415) 353-2528

Email: [email protected]

Learn more about Cardio-Oncology treatment options and how to schedule an appointment:

Resources:

Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921-2964. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318.

Ala CK, Klein AL, Moslehi JJ. Cancer Treatment-Associated Pericardial Disease: Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21(12):156. Published 2019 Nov 25. doi:10.1007/s11886-019-1225-6

Al-Kazaz M, Klein AL, Oh JK, et al. Pericardial Diseases and Best Practices for Pericardiectomy: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84(6):561-580. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.05.048

Altan M, Toki MI, Gettinger SN, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated pericarditis. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(6):1102-1108. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.03.015.

Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(8):1445-1452. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.039.

Chiabrando J, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, et al. Management of Acute and Recurrent Pericarditis: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. JACC. 2020;75(1):76-92. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.021.

European Society for Medical Oncology. Malignant pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. *ESMO Handbooks: Oncological Emergencies*. Accessed August 13, 2024.

Gouriet F, Levy PY, Casalta JP, et al. Etiology of pericarditis in a prospective cohort of 1162 cases. Am J Med. 2015;128(7):784 e1-8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.02.009.

Imazio M, Brucato A, Cemin R, et al. A randomized trial of colchicine for acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1522-1528. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208536.

Maisch B, Rupp H, Ristic A, Pankuweit S. Pericardioscopy and epi- and pericardial biopsy - a new window to the heart improving etiological diagnoses and permitting targeted intrapericardial therapy. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18:317-328. doi:10.1007/s10741-012-9334-4.

Mori S, Bertamino M, Guerisoli L, Stratoti S, Canale C, Spallarossa P, Porto I, Ameri P. Pericardial effusion in oncological patients: current knowledge and principles of management. *Cardiooncology*. 2024;10(1):8. doi:10.1186/s40959-024-00207-3. PMID: 38365812; PMCID: PMC10870633.

Uprety D, West H. Malignant pericardial effusion, or fluid around the heart due to cancer. *JAMA Oncol*. 2024;10(1):148.doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.4500

Yan KL, Lee YJ, and Baik AH. Acute radiation-induced pericarditis complicated by polymicrobial infectious pericarditis in a patient with mediastinal sarcoma: a case report. European Heart Journal: Case Reports. 2024; 8(2)

Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(5):378-382. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80558-x.