Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia, affecting approximately 2.5 million people in the United States. The incidence rises with increasing age, affecting approximately 6% of patients over age 65 and 10% of patients over age 80. During atrial fibrillation the typically organized electrical activation of the upper chambers of the heart [Criley sinus rhythm animation] is replaced by disorganized, chaotic electrical activity [Criley AF animation]. This chaotic electrical activity causes the atria to “quiver” rather than contract normally, leading to stasis of blood in the atria and the potential for thrombus (clot) formation. The site of clot formation during AF is most often an outpunching of the left atrium called the left atrial appendage. If this clot embolizes to the brain, it can cause a stroke. The average stroke risk in AF patients without anticoagulation is 4.5% per year . The chaotic electrical activity in the atria also leads the bottom chambers of the heart (ventricles) to beat rapidly and irregularly.

The symptoms of atrial fibrillation are variable, depending on the individual patient. Some patients have no symptoms at all. Others feel palpitations or an irregular pulse. Many patients experience shortness of breath with exertion. Patients with congestive heart failure, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or aortic stenosis may experience a worsening of their typical symptoms. Another common complaint is fatigue. While the mechanism by which AF causes fatigue is unclear, many patients will feel more stamina in sinus rhythm. Because AF often occurs in older patients, some physicians may attribute fatigue to older age or other cardiac problems. Many patients are often told they should “learn to live” with AF, since it is not life threatening. However, in our experience many symptomatic patients have a significantly improved quality of life if sinus rhythm can be maintained. Therefore, the treatment for AF needs to be individualized for each patient, depending on symptoms, stroke risk, and underlying heart disease.

In the Framingham Heart Study, the strongest risk factor for developing AF was hypertension. Some patients have AF without any hypertension or structural heart disease, and this is typically called “lone AF.” There are also secondary causes of AF including pericarditis (inflammation of the sac around the heart), intermittent heavy alcohol use, lung disease (emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and hyperthyroidism. Initial laboratory tests can often exclude electrolyte abnormalities and hyperthyroidism. Some patients may notice that their AF episodes occur at rest during the night or after eating a heavy meal. This type of AF is often called “vagal” because it occurs when the resting or “vagal” part if the nervous system is most active. Others may develop AF during exertion, or have “sympathetic” AF. Regardless of the pattern of AF occurrence, the treatment is similar. An echocardiogram (ultrasound) is often performed in AF patients to measure left atrial size and left ventricular function, two indices helpful in guiding management.

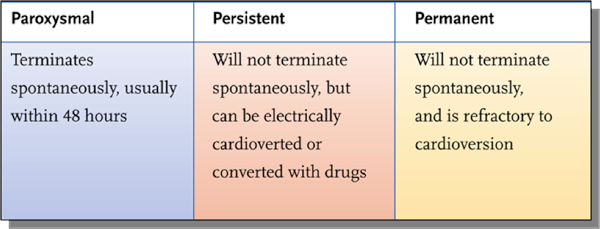

AF occurs in 3 different patterns: Paroxysmal, Persistent or Permanent (the three “Ps”). Most patients initially have AF episodes that start and stop on their own, lasting anywhere from minutes to days. This is called intermittent of “paroxysmal” AF. When some patients develop AF they remain in AF until they receive medication or a cardioversion (“shock”) to restore the normal heart rhythm. This type of AF is called “persistent.” Finally, some patients are left to remain in AF long term with only medications to control the heart rate. Once AF has persisted for > 1 year, it is called either “long-lasting persistent” AF, chronic AF, or permanent AF.