Faculty Spotlight: Nelson Schiller, MD

Echocardiography uses ultrasound waves to create images of the heart, and Dr. Nelson B. Schiller fell in love with this technology just as it was emerging in the 1960s. After nearly half a century of discovering new ways to use this tool, Dr. Schiller, now the John J. Sampson-Lucie Stern Endowed Chair in Cardiology, remains as energized as ever about its power to transform patient care.

Born and raised in Buffalo, N.Y., Dr. Schiller spent several summers during high school in a research program sponsored by Roswell Park Memorial Hospital, the country’s first cancer center. That hands-on experience sparked an interest in medicine, and after graduating from Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., he earned his medical degree from the State University of New York at Buffalo.

During medical school, one of his mentors was cardiologist Dr. Jules Constant. A colorful character and inspiring teacher, Dr. Constant brought several tape recorders to national heart meetings. “He couldn’t go to all the lectures, so he would set the tape recorders up in five or six different rooms, then collect the tapes and listen to them all over the next year, telling the students what he was hearing,” said Dr. Schiller.

One of the lectures was given by Dr. Harvey Feigenbaum, an echocardiography trailblazer. At that time, the technology was quite basic: instead of today’s video images of the heart, a single spiky line represented the heart, and a double spike indicated that there was fluid around the heart – something that was previously impossible to diagnose non-invasively.

“We immediately tried this approach on a patient to see if we could find the fluid, and we did,” said Dr. Schiller. “That got me interested in ultrasound.”

After medical school, Dr. Schiller spent two years working for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as an alternative to serving in Vietnam. He was stationed at the Philadelphia Health Department and focused mainly on tuberculosis. Technically, federal employees were prohibited from outside employment, but his boss strong-armed him into staffing a clinic at the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union.

Dr. Schiller had applied for residency programs, and received a call while he was working at the union clinic. “I heard ‘This is the White House,’ and was so scared!” recalled Dr. Schiller. “I thought I was going to go to federal prison for moonlighting.” It turned out to be a call from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s personal physician, Dr. J. Willis Hurst, who was calling to offer Dr. Schiller a position in a residency program.

Despite the prestigious offer, Dr. Schiller ultimately accepted a residency at UC San Diego, where famed cardiologist Dr. Eugene Braunwald was starting a new program.

Genie on His Shoulder

Dr. Schiller was then recruited to UCSF in 1971 as a U.S. Public Health Service cardiology trainee, and completed his cardiology fellowship. At that time, diagnoses were generally made by X-rays and the new fields of angiography and nuclear medicine, or by brilliant clinicians who sometimes turned out to be incorrect.

Echocardiography was just starting to gain traction as a diagnostic tool. “They brought a machine around and wanted us to try it out, but nobody was interested,” said Dr. Schiller. “I said, ‘I’ll take it to clinic and try it out on my patients.’ The minute I started doing that, I realized that a lot of the patients had the wrong diagnosis. It was amazing, like having a genie on your shoulder, and it got me absolutely hooked.”

In those early days, he and his colleagues captured data with Polaroid photos, a bit like using a stop-motion camera. “You’d get a couple beats, and then you would change the [film] pack,” said Dr. Schiller. Later, strip chart recorders provided a continuous flow of information, and they laid out long strips of light-sensitive paper in the hallways to develop the images.

While he was still a second-year fellow, Dr. Schiller founded what became the UCSF Echocardiography Laboratory at Moffitt Hospital. “People started sending me patients, and then asked, ‘Would you mind staying on the faculty?’” said Dr. Schiller. “At that point I was looking for a job, so I said, ‘Okay, I’ll give it a try,’ – and now I’ve been here 45 years.”

Transesophageal Echocardiograms

Echocardiography evolved from one-dimensional measurements to two-dimensional pictures based on radar technology – a development spearheaded during World War II by a few laboratories, including Varian Associates in Silicon Valley. In the 1970s, Varian was developing advanced ultrasound machines that could look at the heart in two dimensions.

“I told my boss, [then-Chief of the Division of Cardiology] Dr. William Parmley, ‘We’ve got to grab this,’” recalled Dr. Schiller. “We drove down to the Varian factory in Palo Alto and made a real pitch to get that first machine. It was a footrace between Stanford and UCSF, and Varian gave one to each of us. We were very lucky to get our foot in the door, because that was the beginning of the modern era of cardiac diagnosis.”

Dr. Schiller became a consultant for Varian, and was among the first to test out new tools. Among those was the transesophageal probe, which was inserted into a patient’s mouth and down the esophagus to provide clearer images of the heart than could be obtained through the chest wall. He collaborated with Dr. Peter Kramer, a German cardiologist who worked with Dr. Peter Hanrath – an early proponent of this transesophageal approach – as well as with Dr. Michael Cahalan, the recently retired chief of anesthesia at the University of Utah.

“I hated the idea of invading people and having them swallow this horrible thing,” said Dr. Schiller. He and his partners came up with the idea of testing transesophageal echocardiograms on patients undergoing cardiac surgery who were already under anesthesia. “As soon as we did this, we realized we had something really good,” said Dr. Schiller. “You can monitor the patient with really exquisite detail throughout the procedure, and can tell if the repair hasn’t been adequate or something else has gone wrong. Now it’s standard technique everywhere, and has contributed to the safety of cardiovascular surgery.” Transesophageal echocardiograms are also widely used to more accurately diagnose many forms of heart disease.

Doing the Numbers

In the mid-1970s, Dr. Parmley asked Dr. Schiller to digitize and quantitate the diagnostic part of the echocardiography lab – a visionary move given that personal computers were just getting off the ground. “People at this institution always exhibited a lot of foresight,” said Dr. Schiller. He and his colleagues researched how to measure cardiac function more precisely, and developed a computerized database of diagnoses which they continue to use today.

Around 2000, Dr. Mary Whooley – a primary care physician and health services researcher based at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC) – invited Dr. Schiller to collaborate on the Heart and Soul Study, which sought to understand the links between mental and physical health in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Schiller designed the echocardiography portion of the study, using his dictionary of diagnoses to develop a quantitative protocol. He also interpreted the echocardiograms for each of the 1,024 enrolled patients, measuring pulmonary pressure, end systolic volume, and many other variables. Because patients were followed for more than 15 years, the study also measured changes over time – generating a treasure trove of data and more than 150 peer-reviewed publications.

Among other measurements, Dr. Schiller figured out a way to measure the mass of the left ventricle – the lower left chamber of the heart which pumps blood to the entire body. “Anytime the heart is stressed and starts to fail, it thickens and hypertrophies – the muscle gets bigger,” he said. “It’s a sign that something isn't working right or that the heart is overloaded.”

Previously, researchers had only measured the thickness of the left ventricular wall, but that provided limited information. “If I told you the distance from floor to ceiling was so many feet and asked you to figure out what the room looked like, you would have no idea,” he said. “It could be a closet with a high ceiling, or an auditorium. That’s what people were doing with the heart.”

Dr. Schiller’s wife, Ellen, taught Advanced Placement calculus at The Branson School in Ross, Calif. He asked his wife to help develop a formula to accurately estimate left ventricular mass. She did this by plugging in variables for left ventricular wall thickness and other measurements, then mapping them onto a truncated ellipsoid –a bullet-shape cross-section of the left ventricle. “She sat down and did the math, and that resulted in a standard method that’s now in use,” said Dr. Schiller. “She’s on the paper, and it got published. That was a lot of fun!”

Another of Dr. Schiller’s quantitative innovations was expanding the use of Doppler echocardiography, which uses the Doppler effect to determine the speed and direction of blood flow. In particular, Dr. Schiller applied this technology to develop a more comprehensive non-invasive profile of hemodynamics, especially to help diagnose the presence and severity of pulmonary hypertension.

One of Dr. Schiller’s current areas of interest is left atrial function – how well the upper left chamber of the heart works – which he thinks is key to understanding atrial fibrillation, the most common abnormal heart rhythm. He and his Heart and Soul colleagues are also studying biomarkers such as C-reactive protein and high sensitivity troponin, evaluating how elevated measurements affect patient outcomes over five or 10 years.

Caring for a New Type of Heart Patient

Yet another of Dr. Schiller’s innovations was founding the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Clinic in 1985. The clinic developed to serve the growing number of patients who were born with anatomical heart defects who survived into adulthood, thanks to lifesaving innovations in cardiac surgery.

“These patients lived longer, but they weren’t cured,” said Dr. Schiller. “They’d had pediatric cardiologists and were then sent to adult doctors, who sent them to the Echo Lab for diagnosis. Nobody knew what they had, and they were terribly complex.”

At the time, Dr. Schiller did not know much about many of these diseases, but he teamed up with Dr. Norman Silverman, a pediatric cardiology fellow who is now a world expert in the field. “Norm would help me interpret these echoes, and then I would look up these conditions and figure out what was going on,” said Dr. Schiller. “I had never heard of half of these things, because [at that time] there was almost a gentlemen’s agreement that congenital heart disease was not part of adult cardiology. When I was in training, nobody ever mentioned it.”

Learning on the job, Dr. Schiller established the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Clinic, and continues to care for many of these patients today. Some of these patients are now in their 50s, and a few are in their 80s.

A ‘Bright and Shining Star’

Dr. Schiller continues to see patients, conduct research, and train the next generation of physicians and cardiologists. “I can’t imagine having a better time doing what I’m doing,” he said. “I like applying all this to patient care. I look forward to seeing patients and having them not succumb to their conditions, but living with them and getting as much out of life as they can. I enjoy the long-term relationships I develop with them – they’re like family. It’s also very gratifying to get a referral of a complex patient, and trying to solve their problem.”

One of the other great joys of his work is teaching. “I love having residents and fellows in the lab,” said Dr. Schiller. “There aren’t words to describe how good they are. We attract the best people, and so many of them have gone on to positions of leadership in American medicine after they leave.”

He encourages trainees to keep the whole patient in mind when reading an echocardiogram. “I always ask myself, ‘What does this little blip mean in terms of a real person?’” said Dr. Schiller. “How is it going to affect care, drug choices, advice to the patient, and the outcome? These are all difficult questions, but they can be made much easier if you integrate an echo with the anatomy and function of a given individual.”

Dr. Schiller’s clinical work also inspires his investigations. “All good research begins at the bedside, in my opinion,” he said. “Any worthwhile ideas I’ve had came out of taking care of people and making decisions.”

In addition to his work with the Heart and Soul Study, Dr. Schiller established the Research Cardiac Physiology Laboratory (RCPL) at the UCSF Cardiovascular Care and Prevention Center at Mission Bay in 2013, with the help of many individuals and foundations. “I’m very grateful that our research has been made possible by the sustained and generous support of philanthropically minded supporters of our investigative mission,” said Dr. Schiller.

The RCPL lab includes a sonographer, statistician and cardiology fellow. Along with conducting novel studies defining left atrial function during exercise, the laboratory collaborates on projects with many other investigators, including:

- Arrhythmia research with Dr. Edward P. Gerstenfeld, the Melvin M. Scheinman Endowed Chair in Cardiology, and Dr. Gregory Marcus, Endowed Professor in Atrial Fibrillation Research.

- Identifying early cardiac toxicity, in collaboration with the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

- Characterizing left atrial function and its effect on population outcomes, in partnership with the Framingham Heart Study.

- Defining cardiac manifestations of congenital conditions that are associated with sudden cardiac death, in collaboration with Dr. Melvin Scheinman, Walter H. Shorenstein Endowed Chair in Cardiology.

“Dr. Nelson Schiller is an outstanding and innovative researcher, a thoughtful and compassionate clinician, and a superb teacher and mentor,” said Dr. Rakesh K. Mishra, director of the SFVAMC Cardiac Stress Laboratory and associate director of the SFVAMC’s Cardiology Clinics. “He has inspired generations of trainees at UCSF and continues to do so. He is one of the bright and shining stars in the UCSF galaxy!”

“It’s been a wonderful career,” said Dr. Schiller. “I think UCSF will be the number one medical institution anywhere within a very short period of time. It has leadership, a spirit of innovation, and the support of the community. Mission Bay is a city, and the Silicon Valley scene is really helping this institution. I love coming here – it’s almost like watching the creation of the universe.”

In addition to medicine, Dr. Schiller enjoys gardening, playing tennis every weekend with his wife, reading the New York Times, and writing the program notes for the UCSF Chancellor’s Concert Series.

He and his wife have two grown daughters. Their older daughter, Laura, has served as a top aide to some of our country’s most prominent Democratic officials, including First Lady Hillary Clinton, Health and Human Services Secretary Donna Shalala, Senator Amy Klobuchar, and Senator Barbara Boxer, for whom she served as chief of staff for more than a decade. Their younger daughter, Emily, is a clinical psychologist at Kaiser Richmond, where she worked in an intensive outpatient program and was the training director for the postdoctoral residency program. She recently transitioned into a new role as a behavioral health manager, helping her department expand its telehealth platform to improve and facilitate easier access to mental services. Dr. Schiller and his wife are also proud grandparents of an 8-year-old grandson, Jacob.

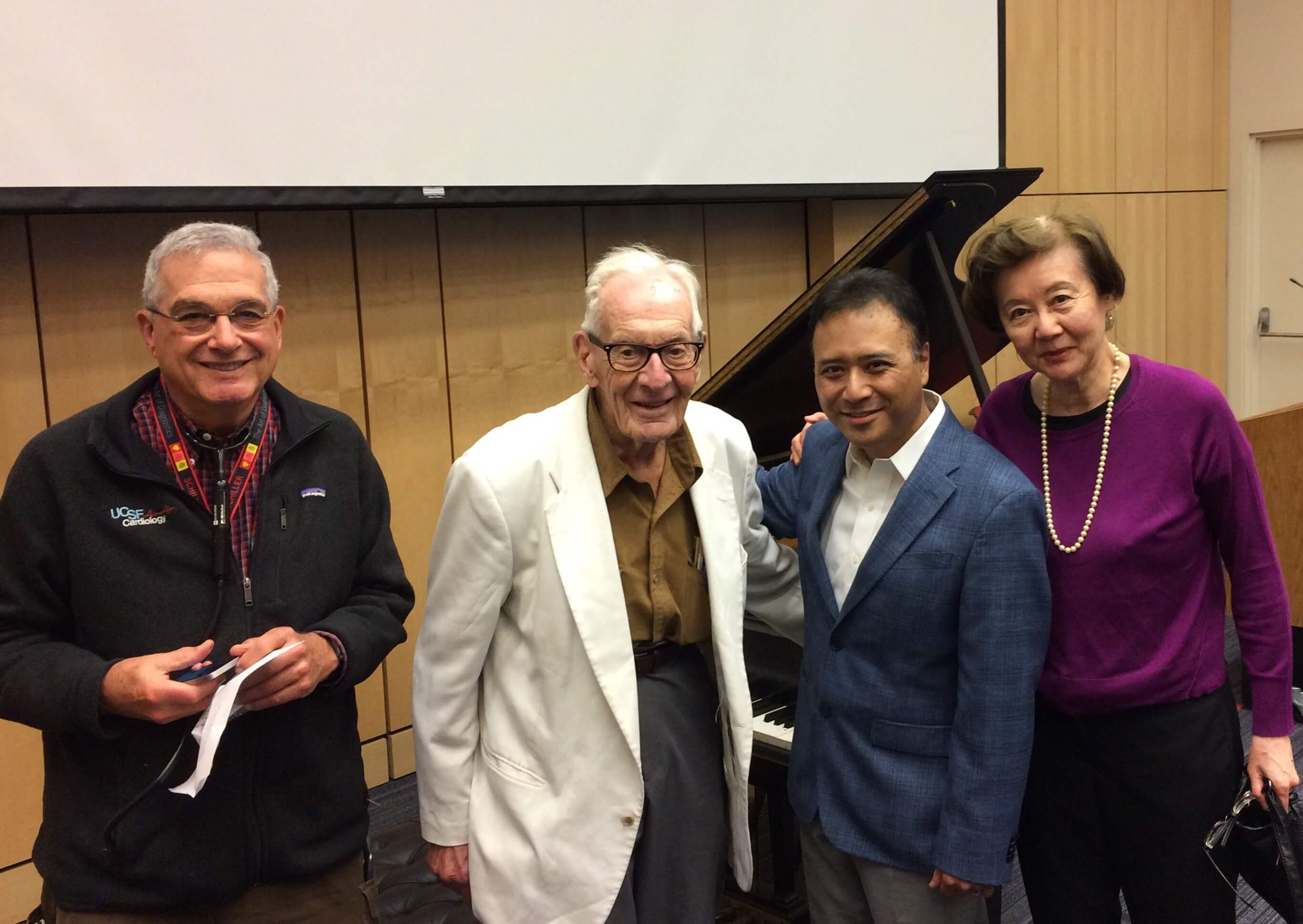

In addition to his outstanding accomplishments in echocardiography, Dr. Nelson Schiller writes the program notes for the UCSF Chancellor’s Concert Series. From left, Dr. Schiller; Dr. John Severinghaus, professor emeritus of anesthesia who originated the first blood gas analysis system; Jon Nakamatsu, gold medalist of the Tenth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition; and Dr. Pearl Toy, professor emeritus of laboratory medicine and founder of the concert series. The photo was taken in April 2018 at a concert honoring the 96th birthday of Dr. Severinghaus.

– Elizabeth Chur