COVID-19 and Health Disparities

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed some of the deepest fault lines in our society, taking a disproportionate toll on African Americans, Native Americans and Latinos. UCSF cardiologist Michelle Albert, MD, MPH is at the forefront of investigating these health disparities and ways to address them.

While these groups have higher rates of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and kidney disease, that is only part of the story. “We know that about 80 percent of health relates to social factors, and only about 20 percent to genetics,” said Dr. Albert, director of the CeNter for the StUdy of AdveRsiTy and CardiovascUlaR DiseasE (NURTURE Center) and associate dean of admissions for the UCSF School of Medicine. “We have two pandemics occurring: a pandemic of racism, and the COVID-19 pandemic on top of that.”

For example, African Americans accounted for 70 percent of COVID-19 fatalities in Louisiana last spring, while comprising only 32 percent of the population. Similarly, frontline health care workers of color in the U.S. and the United Kingdom were almost twice as likely as their white colleagues to test positive for COVID-19.

Socioeconomic factors play a large role. For example, many African Americans and Hispanics are essential workers who take public transportation to their jobs in the food and service industries. Many live and work in crowded environments where it is impossible to physically distance from others. Many also face obstacles to accessing health care.

Photo credit: Elisabeth Fall

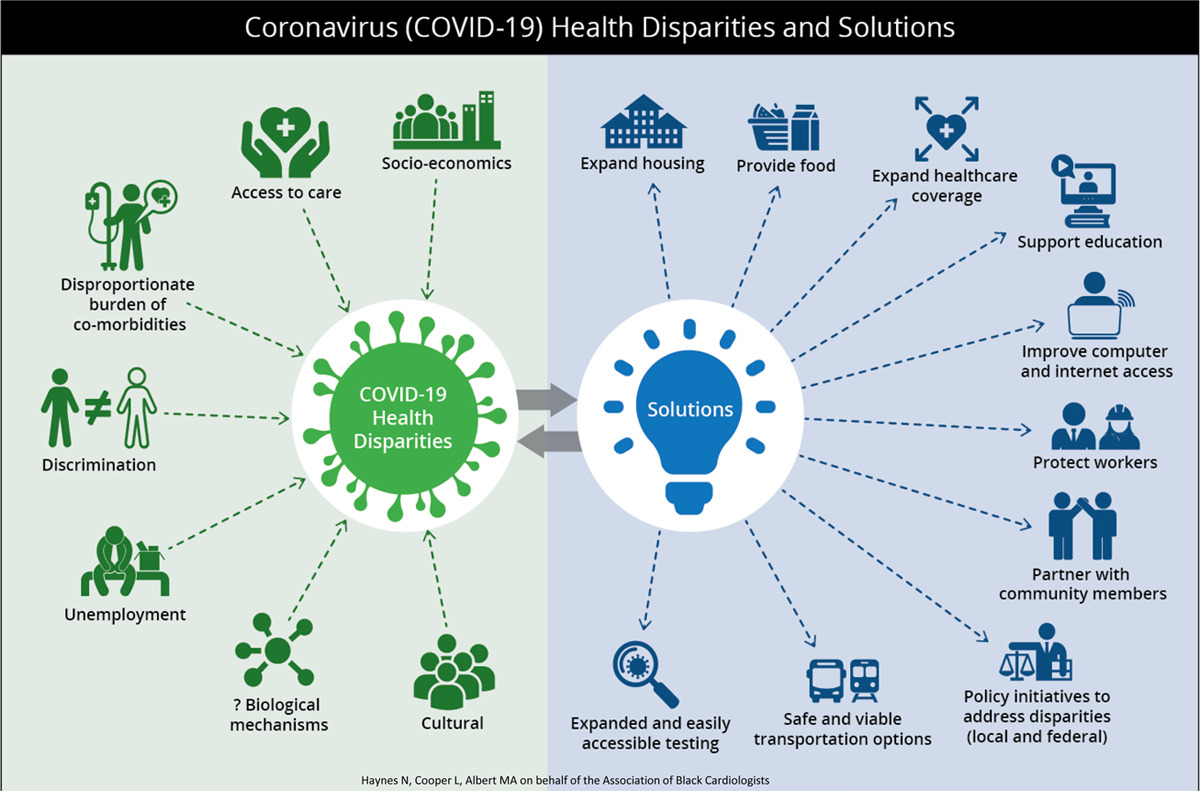

Dr. Albert serves as president of the Association of Black Cardiologists, and she and her colleagues at that organization recently published a paper in Circulation proposing solutions to reduce health disparities: expanding health coverage and access to COVID-19 testing, providing dorm and hotel rooms to people who need to quarantine, providing food for those in need, and providing safe transportation options, among others.

Black Women and COVID-19

Dr. Albert was recently awarded an American Heart Association (AHA) rapid response grant to study cardiovascular complications and mortality in Black women who have been affected by COVID-19. Her team was one of only 10 to receive funding from this highly competitive program, which received 750 applications. Her group includes the UCSF NURTURE Center and collaborators at Boston University, which has enrolled 15,000 participants in its questionnaire-based Black Women’s Health Study.

Dr. Albert and her collaborators will seek to identify risk factors and outcomes related to COVID-19, and to develop targeted interventions. “One question we have is whether there are unique things that pop up among Black women that get lost in other studies, where Black women represent only a small percentage of the study,” said Dr. Albert. She hopes to secure additional funding to understand the longitudinal effects of COVID-19.

“Black women are at the intersection of the worst economic and health disparities that exist,” said Dr. Albert. “They’re the fulcrum of the community and tend to be caregivers not only of children, but also of elderly relatives. They are also more frequently house-hold breadwinners compared to women of other racial or ethnic groups, and are more likely to live in disadvantaged neighborhoods and households, regardless of education or income level. Even in circumstances where Blacks are highly educated, the returns gotten on that investment are substantially less than for their white peers.”

The pandemic has hit close to home: Dr. Albert’s own mother was hospitalized for three weeks with COVID-19. “I knew if we called an ambulance, they would take her to the nearest hospital to her residence and she wouldn’t survive,” she said. “I told my cousins to put her in a car and drive her as fast as they could to a hospital where I knew that she would get great care and have a chance at survival. Social vulnerability includes which hospital you present at. Just because I’m a cardiologist, my family and I are not immune to the effects of racism-based health and economic disparities.”

The AHA recently awarded her the prestigious Population Research Prize in recognition of her outstanding research endeavors using epidemiology and population science. “I want to improve the lives of populations which are at greatest need,” said Dr. Albert.

- Elizabeth Chur, Date Published: Fall 2020