Faculty Spotlight: William Grossman, MD

Over his storied career, cardiologist William Grossman, MD, Charles and Helen Schwab Endowed Chair in Preventive Cardiology, has saved countless lives, championed prevention of heart disease, and broadened our understanding of heart failure. He also wrote an authoritative textbook, and later transformed the UCSF Division of Cardiology.

But what originally drew him to medicine was his own experience of a deeply caring doctor. His childhood physician, Ludwig Cibelli, MD, was a family friend who made house calls whenever little Bill Grossman got sick. “The whole thing was very dramatic,” he said. “My parents stood at the bedside, worried. Dr. Cibelli came with his little black bag, examined me, and listened to my heart with this weird instrument called a stethoscope. I remember listening to my own heart with the earpieces, and thought that was really interesting!”

Getting to combine his interest in science with the opportunity to be an important part of patients’ lives inspired him to pursue a career in medicine. Dr. Grossman earned his bachelor’s degree from Columbia College, then completed his medical degree at Yale University School of Medicine. In medical school, he was fascinated by how the brain was involved in the control of thoughts and emotions, but was disappointed when he got to his clinical rotations in neurology and psychiatry.

“At that time, neurologists were only interested in the anatomy of the brain if someone was having a stroke or a tumor, but nobody at Yale was interested in the brain as a thinking organ,” said Dr. Grossman. “The psychiatry department was totally Freudian, and at that time, they didn’t think the brain was important. It was all about your childhood experiences.”

Neurology’s loss was cardiology’s gain. He completed his internal medicine internship and residency at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, where cardiology was king. “They had a lot of famous guys who had been pioneers in heart disease and heart surgery,” said Dr. Grossman. They included Lewis Dexter, MD, a pioneer in cardiac catheterization; Richard Gorlin, MD, who developed a way to quantify heart valve narrowing (the Gorlin formula); Dwight Harken, MD, the father of heart surgery; and Bernard Lown, MD, who developed the first coronary care unit (CCU). “Cardiology was very attractive, and I decided that’s what I wanted to do,” said Dr. Grossman.

He told his wife, Melanie, how awed he was by the brilliance of his fellow interns. “‘Honey, this is definitely the first time that I’m not in the top half of my class in terms of intelligence,’” Dr. Grossman recalled telling her. “‘If I’m lucky, I’m in the dead middle of the group!’ But after six months of my internship, I realized that while you had to be smart enough to understand the basics of biology, what was really important was taking the time to be thorough and getting all the facts. That’s really worked for me over the years.”

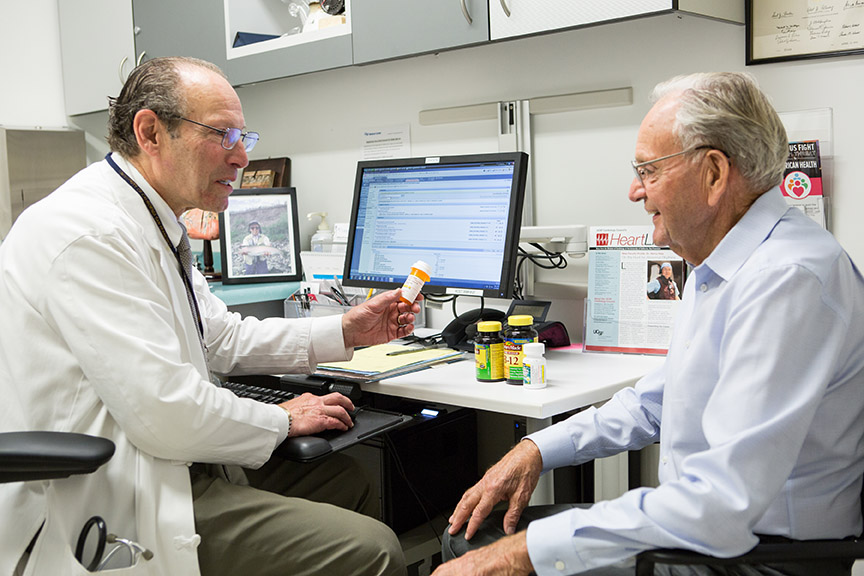

Dr. Grossman cultivated this methodical approach during training. “I talked with the patient and really listened to what they said, making sure I got all the information before coming to a conclusion,” he said. “Often the diagnosis came to me as I was filling out all these forms we had – the history of the present illness, past medical history, review of systems.” Today he is legendary for his thoroughness, asking each patient to bring in pill bottles for every prescription, vitamin, over-the-counter medication, and herbal supplement they are taking.

He also observed endocrinologist George Thorn, MD, who served as chairman of medicine at the Brigham for three decades. Patients came from all over the country to see Dr. Thorn, and often were inspired to make philanthropic gifts to fund his research. One of them was Howard Hughes, which is why Dr. Thorn was the first director of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, following Hughes’s death. “Most trainees were not interested in Dr. Thorn, because you’d go on rounds with him and he’d spend a lot of time talking with his patients and examining them,” said Dr. Grossman. “People wanted more action, more science. But I thought, there must be something going on here – people are traveling long distances to see him. So I watched what he was doing.”

During his training, Dr. Grossman cultivated both an openness to innovation as well as a healthy skepticism of the latest fads. “One of my favorite quotes is from Alexander Pope, which is ‘Be not the first on whom the new is tried, nor yet the last to lay the old aside,’” he said. “There is always some new idea that’s going to cure cancer or abolish heart disease, and some of them are really good – but until they’re proven, you don’t know what’s hiding underneath the surface. You want to bring good things to your patients, but you don’t want to harm them. I take very seriously the Hippocratic oath, which says Primum non nocere – ‘first do no harm.’”

Spirit of Adventure

During his undergraduate years and medical training, Dr. Grossman also had pivotal developments in other areas of his life. The summer after his junior year of college, he and a classmate took a road trip, cruising the highways and byways in a Studebaker Silver Hawk borrowed from his friend’s father. They camped out in state parks to save money, and one hot June evening found themselves in the Evangeline State Park in St. Martinville, Louisiana.

“We saw there was a swimming pool nearby, so we paid our 25 cents and went in,” said Dr. Grossman. “We saw these two attractive young women sitting by the side of the pool, dangling their toenails, so we swam up to them and I said, ‘Hi.’ Melanie looked down at me and said, “‘Hi. Do we know y’all?’ I said, ‘I don’t think so. We’re from New York.’ She opened her eyes wide and said, ‘From New York? What y’all doing way down here?’

“That was it,” recalled Dr. Grossman. “I was gone. People talk about love at first sight, and in retrospect, that’s what it was.” The two young men prolonged their stay. “I would call home on Sundays to speak to my dad, and would say, ‘We’re still in St. Martinville, Dad,’” he recalled. “He said, ‘She must be really something, son!’” After the school year resumed, the two wrote letters almost daily, and married four-and-a-half years later.

“JFK was the first president I was old enough to vote for,” said Dr. Grossman. “JFK said, ‘Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country,’ and he formed the Peace Corps. Melanie and I wanted to go, and we did.” After his internship year at the Brigham, Dr. and Mrs. Grossman spent two years in New Delhi. Dr. Grossman learned Hindi and served as a Peace Corps physician, taking care of Peace Corps volunteers and seeing Indian patients weekly in a small town on the outskirts of New Delhi.

Bitten by the Research Bug

By that point he had decided to become a cardiologist, but was unsure if he wanted to pursue a research career. However, he continued to take meticulous notes on all his patients, just as he had as an intern. Dr. Grossman saw one Peace Corps volunteer who had developed typhoid fever. It seemed odd, since volunteers were vaccinated and received boosters every six months. Then he saw another five cases of volunteers in the same situation. “It was in the early days of these vaccines, and what we found was that these six patients got typhoid fever between four-and-a-half and six months out from their booster,” said Dr. Grossman. “So the vaccine didn’t actually work for six months.”

He wanted to write up his findings. “One of the Indian doctors I knew said, ‘When the British were here, the Lancet was a very big journal for them, and it published a lot of tropical medicine,’” said Dr. Grossman. “So I wrote an article and sent it off to the Lancet, and they took it right off the bat. It was my first article, and they just took it, with no revisions!”

In those days, readers who wanted an article reprint sent postcards to the author to request a copy. “All of a sudden, postcards started to arrive from all over the world – from the United States, England, Europe, everywhere,” recalled Dr. Grossman. “Some people wrote notes on their postcards, and some wrote letters and told me about their own experiences. I thought this was fascinating! That really turned me on to research.”

Dr. Grossman wrote a number of other articles during his time in India, including a report about six Peace Corps volunteers who had ingested cannabis products, which were much more potent than the marijuana available at that time in the U.S. “I got a call from a village where one kid was walking around naked, proclaiming that he was God,” he said. The volunteer had attended an Indian wedding where guests were consuming marijuana edibles. The patient was medically evacuated to a psychiatric hospital outside of Washington, D.C. “The psychiatrist there told me that at least four of these patients had schizophrenic reactions,” said Dr. Grossman. “We didn’t see a lot of acute psychiatric illness in our Peace Corps volunteers, but we did see it in these cases.

“The idea that you could just be a doctor and make observations, and from that you could put together a new piece of knowledge, was very seductive to me,” said Dr. Grossman. “It had a big influence on my career.”

Treating Emergencies, and Preventing Them

After returning to the U.S., Dr. Grossman completed his internal medicine residency and cardiology fellowship at the Brigham. He was particularly drawn to interventional cardiology, a subspecialty that incorporates the same kind of manual dexterity, athleticism and use of specialized tools that he employs as a fly fisherman. “It’s kind of an art,” he said.

Early in his career, Dr. Grossman relished the excitement of performing life-saving procedures in the cardiac catheterization lab. “I loved being where the excitement and action was, with something really juicy like a cardiac arrest or somebody with a ruptured aneurysm,” he said. “You had to get in there and do something aggressive, and could often fix it, which was very attractive to me.”

While he enjoyed the thrill of an acute case, Dr. Grossman also gradually developed an interest in preventive cardiology. “I would meet a patient in the emergency room, take them to the cath lab, and God willing, the patient would get better,” he said. “They would be upstairs in a hospital room, and I would see them every day. I wasn’t one of these guys who was only interested in doing the procedure. I formed relationships with my patients.”

Dr. Grossman remembers one patient in the early 1990s who had angina – chest pain or a feeling of pressure, often caused by narrowing in the coronary arteries. “I did the cardiac catheterization, and he had a blockage in his left main coronary artery, which is about the worst kind of blockage you can have,” he said. After a successful procedure, Dr. Grossman prescribed medications to control the patient’s high blood pressure, but strongly recommended that the patient undergo coronary bypass surgery. “The patient said, ‘I don’t know – I’m feeling better now,’” said Dr. Grossman. “I said, ‘Yes, but you have serious blockages. You should really have this bypass surgery.’”

The patient declined, but continued working with Dr. Grossman after he was discharged. “He had decided to really listen to my advice about medicines and lifestyle,” said Dr. Grossman. “He lost weight and was taking all his medications. His cholesterol got much better and he felt well. Ten years later he was doing fine.

“I would present his case to my medical students and residents and say, ‘In general, you should send these folks to surgery, but I just want you to know that sometimes they do surprisingly well without surgery,’” said Dr. Grossman. “Then a number of studies came out showing that for most patients with blockages in their coronary arteries, medical therapy was as good as surgery.” However, left main coronary blockages were excluded from the trials, because it was considered unethical to randomize those patients to medicine versus surgery. “We’ve learned over the years that people can develop collateral vessels that grow in and feed the artery downstream from the blockage,” he said. Dr. Grossman later published an article profiling six cases in which patients had complete occlusion of the left main coronary artery.

“Over the years, by sending very sick patients home and following them, I found that I was getting more and more interested in taking ongoing care of them like my old family doctor, focusing on prevention where you could accomplish it,” said Dr. Grossman.

Writing the Book

After completing his cardiology fellowship, Dr. Grossman was recruited as director of the cardiac catheterization lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Because patient volume was low, he embarked on community outreach to let patients and referring physicians know that their services were available. Dr. Grossman also started up his research program, and was actively engaged in training fellows.

One frustration was the lack of textbooks about cardiac catheterization. “We had to give the young fellows mimeographed handouts,” said Dr. Grossman. “If they happened to be sick or out on a certain day, they wouldn’t know how to do that procedure.” To remedy that situation, he decided to write a textbook that is now the granddaddy of tomes on the subject – Grossman & Baim's Cardiac Catheterization, Angiography, and Intervention is now in its eighth edition, and has been translated into Japanese, Chinese and Spanish.

At the time, publishing a textbook was not a strategic method of advancing one’s academic career. “Usually you became successful, and then they wanted you to write a textbook,” said Dr. Grossman. “I was writing it at age 34, and I thought the thing that would make or break my career was my research. Would I get NIH grants and publish in prestigious journals? That’s where my focus was. But as it turns out, I’m definitely remembered for this textbook.”

Dr. Grossman invited leading experts to contribute chapters, and also wrote much of the content himself. As both an author and editor, he leaned heavily on advice from his freshman English professor at Columbia. “My professor had said that if you can’t write clearly, it’s usually because you can’t think clearly,” he said. “I had gotten a C or D on my first papers – most of us did. But I learned from that, and took his advice seriously.”

The textbook became enormously popular. “That book put all three of my kids through college, and one through medical school,” said Dr. Grossman. As the publisher was wrapping up the sixth edition, Dr. Grossman remembers receiving a call from his editor, saying that they wanted to change the name of the book, which had been Cardiac Catheterization, Angiography, and Intervention. “I said, ‘Really? It’s had the same title for five editions. Why do you want to change it?’ My editor said, ‘We’d like to call it Grossman’s Cardiac Catheterization, Angiography, and Intervention. When you first wrote it, there was only one book. Now there are several competitive books, and we want to be clear that this is the original, and it’s yours.’ I said, ‘That’s very nice, but isn't that something you usually do when people are dead, like ‘Gray’s Anatomy’?

“For years, I would give a lecture, and people would say, ‘Oh, Dr. Grossman, I didn’t know you were so young,’” he said. “Now when I meet people, I can tell they’re thinking, ‘I didn’t know you were still alive!’”

Discovering New Knowledge

In 1975, after four years at Chapel Hill, Dr. Grossman was recruited back to the Brigham as director of the cardiac catheterization lab there by the new chairman of medicine, Eugene Braunwald, MD. “Dr. Braunwald was a powerhouse in cardiology,” said Dr. Grossman. “I knew about his research, but I had never met him.” In 1980, Dr. Braunwald also became chairman of medicine at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston, and appointed Dr. Grossman as chief of cardiology at that institution, a position which he held from 1981 until 1994.

In addition to growing the division from a rather low-key group to a thriving enterprise, Dr. Grossman also conducted groundbreaking research. One of this main focuses was heart failure – a condition in which the heart is unable to pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs. “During my training, the common belief was that heart failure was due to weakness of the heart muscle,” he said. “The strength of the left ventricle in particular was low, so the heart couldn’t pump enough blood around the body, and the blood backed up. That is one of the causes of heart failure.”

However, while in the catheterization lab performing angiograms, Dr. Grossman noticed that some patients’ hearts were able to squeeze just fine, but had difficulty relaxing. “There are conditions in which the heart contracts well, but relaxes very slowly,” he said. “The blood is trying to get in, but since the heart isn’t relaxed yet, it just backs up. At first, people said this was a rare condition, but it probably accounts for about half the cases of heart failure.” He and others called it diastolic heart failure, because the problem centers around diastole – the part of the cardiac cycle in between contractions, when the heart relaxes and fills up with blood before the next heartbeat. Now the condition is often called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

As part of his investigation into this phenomenon, Dr. Grossman delved into the archives of the Countway Library at Harvard, and was astonished to find that researchers in the early 20th century had also identified this condition – long before interventional cardiology and echocardiography had been invented. “It was humbling to realize that guys back in the 1920s didn’t have any tools, and they were able to figure this out,” he said.

“I think it’s very important for young people to know the importance of immersing themselves in the literature of what went before. You read something and think, ‘I can take that one step further.’”

Dr. Grossman also conducted research on cardiac hypertrophy, which occurs when the walls of the left ventricle abnormally thicken and enlarge. His 1975 article in the Journal of Clinical Investigation about the relation between hemodynamic factors and patterns of cardiac hypertrophy was considered one of the top ten breakthroughs that year. In 2013, he and one of his former fellows were invited to revisit the topic in a retrospective article that described progress in this field during the intervening four decades, and summarized questions for further investigation.

“Dr. Grossman was a pioneer in cardiac hemodynamics and was responsible for the seminal work describing diastolic function and dysfunction, work that fundamentally changed how we thought about diastole, or the ‘relaxation’ phase of the cardiac cycle,” said Jeffrey Olgin, MD, chief of the UCSF Division of Cardiology and Ernest Gallo-Kanu Chatterjee Distinguished Professor in Clinical Cardiology. “He also literally wrote the book on cardiac hemodynamics that has remained the bible of understanding hemodynamics for cardiology trainees – including me!”

Transforming the UCSF Division of Cardiology

In 1994, Dr. Grossman was ready for new challenges, and accepted a position heading up cardiovascular clinical research at Merck & Co. near Philadelphia. He joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and saw patients once a week, but after a year Merck wanted him to give up his patient practice. “I refused,” he said. “I just couldn’t imagine not seeing patients.”

In 1997, Dr. Grossman was recruited as chief of the UCSF Division of Cardiology by Lee Goldman, MD, MPH, then-chair of the UCSF Department of Medicine. “There were a lot of very smart, good people here, as well as excellent research going on in the CVRI [Cardiovascular Research Institute],” said Dr. Grossman.

However, there were a number of challenges as well. During his decade as chief, Dr. Grossman got the Division of Cardiology onto solid financial footing, greatly increased patient volume, and recruited outstanding cardiologists, doubling the number of faculty from about 18 to more than 35.

“I knew we had to attract really bright, energetic young people,” he said. “That was the key, because then it becomes autocatalytic.”

All this, of course, requires resources. Shortly after arriving at UCSF, Dr. Grossman and Dr. Goldman met with prospective supporters at the home of Danielle and Brooks Walker. “We presented our vision of building a world-class cardiovascular center here in San Francisco,” said Dr. Grossman. “That evening, the Walkers and 30 of their guests attending the event signed up to be the first members of the Cardiology Council, promising to help us transform our vision into reality.” The Cardiology Council continues to provide extraordinary philanthropic support for the patient care, research and educational missions of the Division.

Dr. Grossman was pivotal in transforming the culture of cardiovascular research at UCSF, championing the recruitment of physician-scientists who both care for patients as well as conduct cutting-edge investigations into better ways to identify, treat and prevent heart disease. Whereas the clinic and the CVRI had essentially existed in parallel universes, Dr. Grossman worked with CVRI director Shaun Coughlin, MD, PhD, to recruit outstanding scientists who also saw cardiology patients.

When the new Smith Cardiovascular Research Building at Mission Bay was in the planning stages, Dr. Grossman advocated to co-locate the main clinic of the UCSF Cardiovascular Care and Prevention Center in the building. This supports translation of lab discoveries into clinical treatments, and also facilitates serendipitous interactions and collaborations between clinicians and scientists.

Building on his longstanding interest in preventing heart disease, Dr. Grossman also established the Center for Prevention of Heart and Vascular Disease with generous support from the Charles and Helen Schwab Foundation. The team of cardiologists sees patients who have had a heart attack or stroke, or are at risk of developing heart disease. By conducting in-depth histories and physical exams and accessing state-of-the-art diagnostic tools, cardiologists work with patients to develop tailored plans that help them manage their conditions and have the best possible quality of life. Patients can also meet with a registered dietician, and can be referred to the UCSF Cardiac Rehabilitation and Wellness Center, a medically supervised program for adults with heart disease that provides exercise, education and emotional support.

Dr. Grossman is beloved by patients, who appreciate his thoroughness, depth of experience, sense of humor, and the way he makes himself available when urgent situations arise. He also takes a genuine interest in their lives, families and hobbies.

Dr. Grossman said that in the long arc of his career, what he has accomplished at UCSF has brought him the most satisfaction. “I think if I had come here earlier, I probably would have failed,” he said. “I learned a lot during my career that made it possible to see how to solve these difficult problems. What I’ve been able to do at UCSF is probably the most important thing that I’ve been able to contribute.”

“Dr. Grossman’s leadership as chief of cardiology has enabled the Division to grow and become one of the top cardiology divisions in the country,” said Dr. Olgin. “His visionary approach to fundraising was on the leading edge and has provided a necessary source of revenue as more traditional sources such as NIH funding and clinical revenues have been on the decline. Moreover, his model for providing personalized, high-touch clinical care has transformed all of the clinical care in the Division of Cardiology.”

Outside of medicine, Dr. Grossman has many interests. An avid fly fisherman, he travels the world in pursuit of the next great catch. He loves to sing, and has been a member of the Golden Gate Symphony Chorus for the past 20 years. He and his wife, a retired social worker, have three grown children: Jennifer, CEO of a think tank; Edward, a technology executive; and Jessica, who trained as an obstetrician-gynecologist and now leads a women’s health company. They also have four grandsons, who uphold the family tradition of fly fishing.

– Elizabeth Chur