Alcohol: Heart Friend or Foe?

"Alcohol is the most commonly consumed drug in the world,” said cardiac electrophysiologist and epidemiologist Gregory Marcus, MD, Endowed Professor of Atrial Fibrillation Research. “About 85 percent of Americans consume at least some alcohol, which is far more people than take statins. Yet incredibly, we do not currently know the best advice to give patients regarding alcohol consumption.”

There is some evidence that drinkers may have a lower risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular diseases. However, the literature suggests that those who drink more alcohol increase their risk of developing atrial fibrillation, the most common irregular heart rhythm.

Given such mixed findings, what’s a doctor – or a patient – to do? Dr. Marcus and his colleagues are conducting innovative research to answer this complicated question.

Rewiring the Heart

Doctors coined the term “holiday heart syndrome” to refer to otherwise healthy patients who drank to excess on holidays, then developed atrial fibrillation. This arrhythmia occurs when the atria, or the upper chambers of the heart, quiver or beat in a chaotic way, rather than pumping in a coordinated fashion.

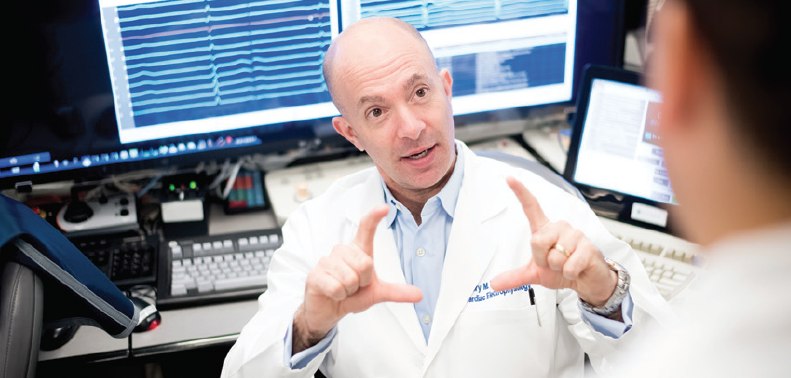

“It’s been really unclear how much alcohol is needed to produce an arrhythmia, and whether it’s an acute or a cumulative effect,” said Jeffrey Olgin, MD, chief of the Division of Cardiology and Ernest Gallo-Kanu Chatterjee Distinguished Professor in Clinical Cardiology.

He, Dr. Marcus and another UCSF electrophysiologist, Vasanth Vedantham, MD, investigated how alcohol affects the electrical properties of the heart. One set of lab experiments studied the acute effects of alcohol, akin to binge drinking. They removed hearts from healthy rats, keeping these hearts alive and beating for hours by nourishing them with an oxygen-rich solution. The researchers added increasing doses of alcohol to the solution and measured the electrophysiologic effects.

At the middle dose, about half of the hearts went into atrial fibrillation, and at the highest dose – the rat equivalent of the drunk driving threshold – they all did.

Alcohol made the heart vulnerable to atrial fibrillation in two ways. First, it shortened the refractory period – the time it takes heart muscle cells to recover so they can accept the next electrical signal telling them to beat again – but did so in a non-uniform way across the atria. “Some cells were early and others were late,” said Dr. Olgin. “If everybody is ready at the same time, it’s much harder to induce atrial fibrillation, but the more heterogeneous that is, the more prone the heart is to atrial fibrillation.”

Second, acute exposure to alcohol slowed conduction velocity – the speed at which electrical signals move through the heart – which is another risk factor for atrial fibrillation.

Moderate Drinking, Profound Effects

Another set of experiments studied the effects of chronic alcohol exposure, similar to modest but consistent drinking. The researchers added alcohol to the rats’ drinking water for six months, producing a blood alcohol concentration similar to that of a 175-pound man after one and a half drinks. Researchers stopped giving alcohol to the rats a day before conducting experiments to ensure they were measuring only chronic, rather than acute effects of alcohol.

Dr. Olgin and his colleagues found that 95 percent of the rats were vulnerable to developing atrial fibrillation, compared to only 10 percent of teetotaling rats who drank plain water. “Interestingly, we saw the same electrophysiologic changes that predisposed rats to atrial fibrillation with chronic exposure as we did with acute exposure,” said Dr. Olgin. “Even though the alcohol levels were relatively moderate, they had profound effects.”

The team also found that the harmful impact of both chronic and acute drinking did not go away, even after a period of abstinence. “Whatever the alcohol is doing has irreversible effects, or a ‘poisoning effect,’” said Dr. Olgin. “It was surprising that even when we removed the exposure, the effects were still present at the cellular level, and the normal state never returned.” Their discoveries will be published soon in the journal Heart Rhythm.

With additional support, Dr. Olgin would like to study whether a longer period of abstinence would reverse the effects of chronic drinking, and to learn more about the effects of intermittent binge drinking. UCSF is one of the few places to conduct electrophysiologic research on the cardiac effects of alcohol. “These are hard experiments to do,” he said, noting that the

UCSF Division of Cardiology has the specialized expertise and tools needed for these studies.

“I’m always reluctant to draw con-clusions from rodent models to humans, but this certainly gives me a little more pause,” said Dr. Olgin. “We need a lot more work to really understand how relevant it is to humans.”

Mysteries of the Human Heart

Dr. Marcus is spearheading efforts to do just that, and has launched a number of ambitious clinical studies, including:

Getting to the heart of the matter: Dr. Marcus and his colleagues recently completed a clinical trial of 100 patients with intermittent atrial fibrillation who underwent ablation. That procedure uses catheters to strategically burn small areas of the heart, short-circuiting abnormal electrical signals that cause arrhythmias. Volunteers could not be teetotalers or heavy drinkers.

Electrophysiologists measured the electrical activity of the heart at the start of the procedure. Then half the participants were randomly selected to receive an intravenous infusion that induced a blood alcohol concentration of 0.08%, the drunk driving threshold. The other half received a placebo infusion. Neither the patients nor the electrophysiologists knew which infusion was given.

Electrophysiologists measured whether the infusion changed electrical properties of the heart, including refractory periods and conduction velocity. Both may be important in atrial fibrillation, and the measurements paralleled the experiments performed in Dr. Olgin’s animal work. At the end of the procedure, they used an adrenaline-like medicine as well as rapid electrical stimulation of the atria to see if patients who received alcohol were more likely to develop atrial fibrillation than those who received the placebo.

Dr. Marcus and his team are currently analyzing the data and look forward to publishing their discoveries. “To my knowledge, this was the first double-blind randomized controlled trial to assess the immediate effects of alcohol on atrial fibrillation, and one of the very few double-blind placebo-controlled trials of alcohol related to heart disease,” he said.

Atrial fibrillation in real life: Dr. Marcus is also studying people with intermittent atrial fibrillation as they go about their everyday routines. He gives them a wearable patch that continuously records their heart’s electrical activity through an electrocardiogram (EKG), as well as wrist and ankle sensors that monitor alcohol levels derived from their sweat. Participants pushed a button on their patch whenever they drink, and periodically complete finger stick tests that quantify heavy alcohol consumption.

“The idea is to look at real-time relationships among ambulatory, free-living individuals between alcohol consumption and atrial fibrillation, which has never been done before,” said Dr. Marcus. “In the past it was very difficult to look at discrete episodes of drinking as they relate to discrete episodes of atrial fibrillation, but now we have technology that makes that possible.”

Test your trigger: Yet another ongoing investigation is the Individualized Studies of Triggers of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation (I-STOP-AFib) study. Supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), people can participate from anywhere in the world. They receive an AliveCor Kardia device, which pairs with volunteers’ smartphones to record their EKG.

Half of participants are randomly assigned to track their atrial fibrillation for 10 weeks, responding to daily text messages asking whether they were symptomatic, how they slept the previous night, and their current mood.

The other half are invited to do an “N-of-1” trial, where they are the single subject of their own investigation. They choose a possible atrial fibrillation trigger, such as alcohol, caffeine, lack of sleep or dehydration, and are instructed each week whether to test their trigger or avoid it – for example, by drinking red wine, or abstaining that week. After six weeks, they receive a calendar showing them their atrial fibrillation episodes and the likelihood that the trigger was associated with their atrial fibrillation.

The severity of atrial fibrillation will then be compared between the two groups, testing the hypothesis that individuals engaging in their own customized trial to evaluate their own proposed trigger can reduce their atrial fibrillation severity and improve their quality of life.

Enlarged hearts: Dr. Marcus and his team evaluated data from the Framingham Heart Study, a multigenerational study that analyzes family patterns of cardiovascular disease. They found that heavier drinkers had an enlarged left atrium, which is associated with several adverse events, including atrial fibrillation. They then showed that alcohol-associated increases in left atrial size statistically explained a substantial proportion of the future atrial fibrillation that was observed. They published their research in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

“High blood pressure can contribute to atrial enlargement, but this study offers one other potential explanation,” said Dr. Marcus. “It’s very likely that some people are more or less prone to alcohol-induced atrial enlargement. We still need to figure out other contributing factors, which could include genetics and [environmental] exposures.”

- Elizabeth Chur, Date Published: Fall 2019